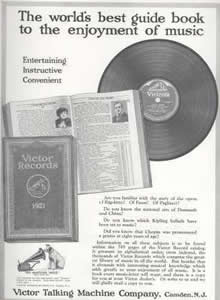

Yet because music was now available almost anywhere, any time, it was now theoretically possible for people to be exposed to a much wider range of music, or to listen to more music than they had in the past. Performers who resided in Europe, for example, could now easily be heard anywhere in the world where there was a phonograph player. Some believed that the mass-duplication of the best available music would result in a process of social uplift. In practice, most people in the United States and Europe continued to buy popular music of the kind that few reformers considered uplifting, and ignored what they called “good” music. While in Western Europe “good” music had more of a popular appeal, in the United States the improvement of the public’s taste became something of a reform movement, backed both by music critics and the recording industry. Record manufacturers such as Victor, Columbia and Edison’s company responded by advertising good music more heavily and offering a wide variety of it in their catalogs. Some record companies, such as Victor, set up departments to promote music appreciation in colleges and schools, developing special packages of records and programmed courses of instructions. Historians have also countered the argument that the phonograph degraded musical taste by noting that “good” live music was not always readily available to millions of people in nations like the United States, who lived outside major cities. The phonograph provided a link to urban culture good and bad, including the “serious” music preferred by highbrow music critics. However, by the time it was possible to track record sales according to the type of music, it was clear that the public still preferred popular music. Record companies did nothing to discourage the sale of popular recordings, which largely supported their business.