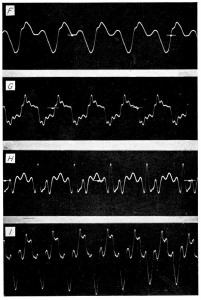

Phonautograph recordings, called “traces”

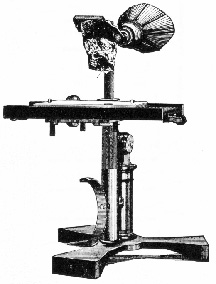

Phonautograph

There was sound recording before the phonograph, but not sound reproduction. In 1856 or ’57, years before the invention of the phonograph, French inventor Leon Scot demonstrated the Phonoautograph system for recording sounds. It used a diaphragm sensitive enough to respond to strong sound waves, stretched across the narrow end of a metal cone or “horn,” and attached to a fine stylus, which pressed against a moving glass cylinder (later flat glass plates would be used by others). The glass cylinder was coated with black carbon (smoke) and rotated, recorded sound as a wavering line. It was then possible to view the shape of the audio wave with the naked eye.

Bell’s Ear Phonautograph

The Phonautograph was apparently manufactured for some decades afterwards and used as a scientific instrument for studying sound. Thomas Edison, who would invent the first successful sound recorder/player, apparently owned one, as did telephone inventor and acoustics expert Alexander Graham Bell. Searching for a more sensitive, accurate sound recorder, Bell modified Scot’s basic design to use a human eardrum and ear in place of the flexible diaphragm.

In April of 1877, a few months before Edison’s invention, Frenchman Charles Cros wrote a description of a machine that he said record and reproduce sounds. Although he failed to patent or demonstrate the device, he deserves credit for the insight that the phonautograph’s recording process could be modified to play back sounds.