Sound recording has been a part of our culture since the late 19th century, gradually becoming more important. At the time of its invention, listening to the recording machine was a startling experience. Edison once recalled how taken aback he was when the prototype tinfoil phonograph actually worked. The ability of a machine to capture the human voice was an astonishing thing to people of the time. Shortly after first using the crude tinfoil recorder at his rural laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey, Edison took advantage of the proximity of New York City (about 50 miles away) to demonstrate it to the public. After hearing it in the offices of the New York Times in December, 1877, a witness wrote that “it is impossible to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the idea that his senses are deceiving him.”

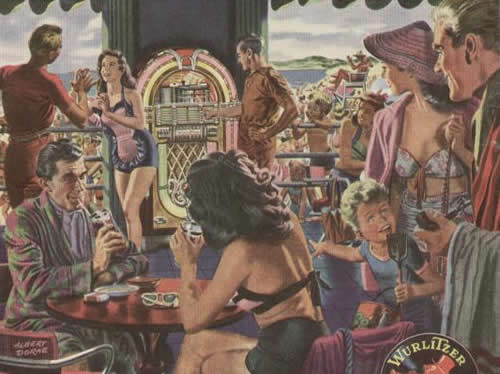

Yet the novelty soon wore off and the main commercial application of the phonograph-office dictation-fell flat. After achieving only limited acceptance as an office dictation machine in the late 1880s, the enterprising manager of the Pacific Phonograph Company set up the first coin-operated phonograph in a saloon in late 1889. While capable of playing only one song, this proto-jukebox helped launch the modern music industry. What Pacific Phonograph had innovated was the idea of using the phonograph to play back commercially made recordings, following the examples of the coin-operated player piano, music boxes, and other arcade-type entertainment technologies. Louis Glass of Pacific Phonograph reported to his business associates in 1890 that each of the two coin-operated phonographs he installed had generated about $1,000 in five months, all the more remarkable because the money was gathered five cents at a time.