The phonograph, graphophone and other players purely mechanical devices through the 1920s. However, in 1924, Columbia began experiments with a new technology developed by the Western Electric Company (the division of AT&T that made telephones and related equipment). Western Electric’s recorder used electronic amplifiers to drive an electromagnetic cutting head, rather than relying on the acoustic horn. The result was a louder, clearer record. In the beginning, the record players still relied on acoustic playback with a horn, but as the home radio became popular, it became more common for people to purchase record players that had electric motors and electronic amplifiers. Some of them had a built-in loudspeaker, while others plugged into specially equipped radio sets and played through them. While some said the new “Orthophonic” records sounded harsh, they soon dominated the market.

Edison electromagnetic record cutter (courtesy Edison National Historic Site)

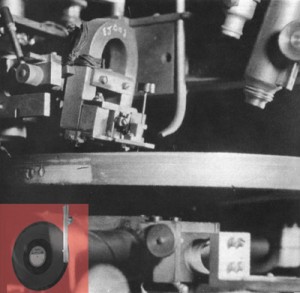

“Transcription” recorder (courtesy Lib. of Congress)

“Transcription” recorders like the one here were a later variation of the basic electrical recording technology. In this type of recorder, electrical signals are delivered to the electromagnetic cutting head, which is carried in a lathe-like mechanism (the operator has his right hand on the lathe).Edison, who had experimented with a form of electrical recording from the beginning, created his own version of the technology as well. Shown here is a close up of the machine from the side. Visible in the center is the large, heavy platter, the cutting head with its horseshoe-shaped electromagnet armature (left) and a microscope for observing the groove.